Hanging In The Air

Such a dainty designer

With the tiniest wand

She will always make sure

That it’s just so perfect and grand.

I’m not a friend of spiders

And their not friends to me

I wonder why God made them

But then sometimes I see

As I watch them spin their many webs

A purpose He surely had

They catch a lot of bugs for us

Some bug are very bad.

HOW A SPIDER GETS OUT OF PRISON.

Much amusement and information in regard to the habits and structure of spiders can be given to one or more children by securing a stick upright in a dish of water, placing on it a spider. Allow the dish to stand in a draught of air, with some article of furniture near, upon which he can throw his web when he finds that is the only way he can escape from the prison. His antics in trying to get away from the pole — which to him is not a liberty-pole—are very funny to watch. He will stretch out one foot, and when it touches the water, he will shake it as pussy does when she walks in the wet grass. After several unsuccessful attempts to effect an escape, he will scamper to the top, and be-gin to whirl around like a spinning wheel — as he is, inside — then throw out a line, and as soon as the air has carried it to a resting place, he will begin to try its strength—as an elephant does a bridge that crosses a stream and he fears will not bear his weight—first with one leg and then the other; if not strong enough, he goes back—not as the elephant, through the water—but to send from his body a little more material to make it secure; and when the bridge is completed he will scamper across, delighted with the liberty he has earned.

—Select

Spiders

Spiders are everywhere, except in the Antarctic where there is snow and ice. They are full of venom and they use their fangs to inject that venom into the skin of their prey or enemies. Spiders have eight legs and they don’t use muscles to bend them but have hydraulic pressure for moving their legs. But the jumping spider in order to make his long jumps use his interior muscles and each leg has 7 sections. Their abdomens have spinnerets that produce silk. Spiders do not have antennae. Most spiders have four pair of eyes. Spiders eat liquids so some kinds of spiders will pump the liquids out of its prey and other kinds will pulverize the food and then take the juice out.

When you read about the mating of spiders it is quite an interesting process because the mother ends up eating the daddy in some species and some of them lay 3,000 eggs in one area and some of them are in silk egg sacs. So it is easy to see why the world is so full of spiders.

All different colors of spiders will surprise you in your walks and in your work. Suddenly you see them and as soon as they see you most of the time they will dash for the corner of something to hide in. Most spiders do not live very long but the tarantulas can live to be 20 years old and can have a 10inch leg span.

Spiders

SOME THINGS ABOUT SPIDERS

AND THEIR WAYS.

SPIDERS rank among the most interesting animals in the insect world but it is not needful that more than a general description be given of a creature so well known. It may be observed, however, that the body is composed of two pieces, and the legs are generally eight in number. Each limb has seven joints, and the foot usually terminates in two claws; but some spiders have only one, while others have three or four. At the base of each jaw is a feeler, or palp, with little claws at its tip. The spider has six or eight eyes, and its skin is rather leathery and horny, sprinkled over with hairs and little spines.

The name in natural history for this insect is arachne, which term also includes scorpions and mites. There are some ten special varieties of spiders, and they are around in all parts of the world, but are largest in warm countries. Being carnivorous in their habits, they devour their prey alive. Spiders are very fond of fighting, the victorious party commonly devouring the other. They are very cleanly in their habits, and spend much time in cleaning themselves from dust with the toothed combs and brushes which nature has attached to their limbs.

Tarantulas, also, belong to the spider species. This variety makes no web, but wanders about for its prey, which it runs down with great swiftness. Its den is made in crevices and holes which it neatly lines with silk of its own manufacture.

Spiders generally hatch but one brood in a year. The eggs are carefully protected in little silken bags, or cocoons. The female spider lays nearly a thousand eggs in a season. The mother is quite affectionate to her young family, and in return for this maternal care her little ones frequently devour her alive. The males and females live separately. The latter are the ones most frequently seen, and are much the larger.

Spiders can endure long fasts, and in this climate they remain torpid during winter. Some of them live several years.

Though objects of general aversion from their cruel habits and dismal haunts, yet they display an instinct which amounts almost to reason.

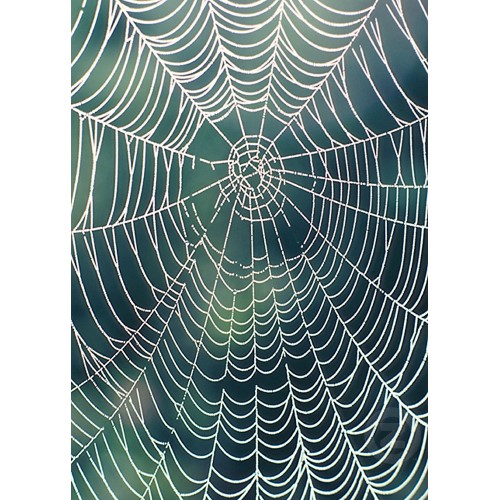

The most remarkable office of spiders is that of weaving their webs by means of a silken thread drawn from fleshy warts on the under side of the abdomen. These spinning glands, called spinnerets, are from four to six in number, and contain thousands of delicate openings, from each of which descends a thread so thin as to be invisible to the naked eye until all are united in one. One set of these warts, or spinnerets, produces threads, which are glutinous, while another set furnishes those, which are smooth.

In spinning their webs, spiders show much perseverance, and great ingenuity.

Recently a spider managed to fasten a silken cable across a river more than a mile in width! They perform such feats in the following manner: When they wish to go from tree to tree, or cross a stream, they let go a thread from their spinnerets in the direction of the wind, and when their delicate sense of touch tells them it has reached an object, they pass over it.

In this way they travel long distances without descending to the ground, a multitude of tiny cables being seen on dewy mornings of spring and autumn. Some small gossamer spiders even speed through the air buoyed up by their fragile threads. Mr. Darwin, in the journal of the voyage of "The Beagle," says that when anchored in the river La Plata, sixty miles from the shore, he has seen the rigging covered with cobwebs, and the air full of pieces of web floating about. The spiders, however, when they struck the ship, were always hanging from single threads.

The beautiful ray-like webs, which we commonly see, so like a figure in geometry, as shown in the cut, are made by a variety of spiders called Epeiridoe, from the Greek word peird,"to affix." This species includes the common Garden Spider. How nicely they affix their webs to a limb, or the angle of a window!

Savage and unsocial as spiders are, they are capable of a certain amount of domestication. Pelisson, a prisoner in the old French Bastile, had a pet spider which came regularly at the sound of a musical instrument to get its meal of flies; and a spider-raiser in France is said to have tamed eight hundred, which he kept in a single apartment for the silk made from their gossamer threads. Spiders readily learn to take food from the hand or a pair of forceps, or water from a brush, and will come to the mouth of their bottle and reach after it on tip-toe.

The spider's supply of silk seems to be limited to sufficient to make six or seven webs in a season. The thread is very strong and fine, and one of its uses is for the division of the micrometer in astronomy.

According to Louenhoek, the great naturalist, it takes four millions of the extremely delicate threads to make a thread as large as a human hair. And each thread of the spider as used in the web is made up of thousands of smaller ones.

A CURIOUS thing in the natural history of spiders is their power of reproducing their limbs after they have been broken off. In such cases it is never a part of a limb which is reproduced; but if a portion is removed, the wise spider proceeds at once to throw off the residue; and after the next molt behold the entire missing limb again appears!

Spiders' webs have been manufactured into a delicate fabric for dresses and gloves; but it is said that to obtain one pound of spiders' silk, the webs of six hundred thousand spiders would be needed. Probably the production of silk from spiders will always be more a matter of curiosity than of utility. But spiders serve one important purpose in the economy of nature, they catch an abundance of flies and insects by their geometrically constructed webs, and, in turn, they are devoured by birds and reptiles. And, disgusting as it may seem, they form a part of the diet of barbarous peoples, as the Indians, Africans, and Australians. Spiders' webs are also in high repute among physicians for staunching the flow of blood from wounds.

We have already remarked that there are a number of species of the spider family. One class, called Natantes, or Swimmers, are water-spiders. Such are the nimble little water-skippers shown in the engraving. This variety are wholly aquatic in their habits. They spin a cup-like web, which answers the purpose of a diving bell.

They can readily exhaust the air from this miniature web-cup, which is about half the size of a common acorn, and then descend beneath the surface to feed on water insects below; or when they wish, come to the top to disport on the water. Their tiny hairs keep their bodies from becoming wet, and in their nests in the water they are as dry as if they were in a hole in the wall.

One species of spider, known as the Attidce, i. e., Jumping Spiders, makes no web,

but wanders in search of its prey. It is common in summer on the walls and windows, basking in the sun. It crawls stealthily up to flies, and jumps with great accuracy upon its victims. Before leaping upon a fly it fixes a thread to secure itself from falling. Mr. Livingston mentions a South African spider of this variety which can leap a foot. Another species is called Thomisidce, or Crab Spiders. Some of them seem to walk better sidewise than forward. The large crab spider of South America is able to leap upon and destroy humming-birds and lizards. That part of its victim which it does not eat, it suspends by a cable from a limb for future use. This spider is about three inches long, and its legs extend over a space of eight or ten inches.

The Lycosidce, or Running Spiders, have long legs, and are very active, living in open places, and catching their prey with-out webs.

The Agalenidce, another variety, make flat webs, with a funnel-shaped tube at one side, in which the spider remains waiting for his prey.

The Mygalidce includes the largest spiders known. They live only in warm countries. They have marked anatomical differences from the other families of spiders.

The long-legged cellar spider, called the Pholcus, has a curious habit of hanging on a cable by its legs and whirling round so fast that it can scarcely be seen.

The distinguished naturalist, Walckennser, divides all spiders into five different groups as follows : 1. Hunting Spiders; 2. Wandering Spiders; 3. Prowling Spiders; 4. Sedentary Spiders; And, 5. Water Spiders. Daddy Long-legs, frequently called Grandfather Graybeard, is of the spider species. Little cow-boys frequently catch them and make them point in the supposed direction that the cows are, before going for the evening herd.

Spiders have the bad reputation of being animals that bite; but Mr. Emerton, a very careful writer about their habits, says, " Not- withstanding the number of stings and pimples that are laid to spiders, undoubted cases of their biting the human skin are very rare; and the stories of death, insanity, and lameness from spider-bites are probably all untrue."

The lives of pious persons have been saved in times of persecution by a spider spinning his web across the entrance to the cave in which they were secreted, their perscutors thinking that no one could have entered without tearing away the web. In the Holy Scriptures the little spider is referred to as an emblem of industry.

G. W. AMADON.

Spiders

A TALK ABOUT SPIDERS.

OH, Bertie, here's a great big, horrible spider right in our corner! Get Sis to kill it."

"Oh!" screamed little Katie, "I'se faid."

"Ah!" said Albert,

"I'm not afraid; I'll kill it."

It was a rainy day, and their mother had let the children play in the attic.

It was such a nice playroom, with its clean, bare floor, its queer little high

windows, and the fine places for hiding behind old chests and boxes! But

now their play had come to an end, for the spider had given them a great fright. Jennie, their "big sister," entered by the door, and, laughing at the "dear little goosies" (as she called them), she said, "No; we won't kill it; it is a harmless little creature. But come, sit down and let us watch it spinning its pretty web. Who made the spider, Mary?"

"God."

"Yes; and the Bible tells us that 'all his works are wonderful,' and that 'all his works shall praise him.' When we go down stairs, Sis will show you a dead spider that she has, through a microscope, and you will see how wonderfully God has made it, and how it praises him by showing us his great power and goodness. In the middle of the spider's body there is a strange little spinning-machine that spins the web. Every thread of that web you see is formed of hundreds of smaller ones finer than the finest silk. As the web runs out, the spider takes hold of it with its hands and fastens it where he wants it to go."

"You mean feet, Sis? " said Albert.

"No; I mean hands," said Sis; "for it really has hands, with two fingers and a thumb. When we look at the spider through the microscope, you will see that he wears a beautiful velvet coat, much better than your little dress, Katie, for it does not hurt his coat to get wet, and it never wears out either."

"I don't see his eyes, Sis," said Mary, who had crept close to the web, and was watching him.

But he sees yours, Mary, for he has four times as many as you have; and he can do more than you can, for he can see on three sides of his head at once. He has eight beautiful eyes two on the top of his head, two in front, and two on each side."

"My!" said Albert, "wouldn't it be jolly to have eight eyes when we go with papa to the 'Zoo'? We can't see half enough with two eyes. But look, Sis! He's standing still. I wonder if he hears us talking about him?"

"Yes, Bertie, he hears us, although he has no ears. That sounds strange, doesn't it? You know that sound is made by little waves in the air striking against your ear. Well, in the spider these little waves strike against the hairs on its legs, and it hears in this way. So that instead of giving the spider ears, God has made this wonderful arrangement by which it hears with the hairs on its legs. It can hear the slightest noise, and I suppose it is just as well satisfied as if it had a pair of ears. There are several hundred kinds of spiders. There is the 'house-spider' and the 'garden spider;' the 'water spider,' that makes a little diving-bell and lives in it under the water; and a very curious kind called the 'tiger-spider,' because it is striped like the tiger. It digs a little cave in the earth to live in, and festoons it with fine curtains of web, and at the entrance makes a door that has hinges to it and shuts with a spring, so that when its enemy, the digger wasp, comes, he can shut himself in and be safe.

"Another kind of spider digs a burrow into the earth about seven inches

deep, and then above the ground he builds a pretty five-sided tower of

sticks, each stick about an inch long.

Then he fringes it on the outside with pieces of moss and grass, and lines it

on the inside with beautiful web as soft and smooth as silk. If you, Bertie,

wanted to become an architect when you are grown, you would have to study a long while before you could build a beautiful house; but this little tower-builder never had to learn his profession. God gave him this wonderful knowledge by which he can build this pretty house without being

taught.

"Then there is another kind called the 'gossamer-spider,' and it is quite a

traveler, for it takes long journeys through the air, although it cannot fly.

Now, how do you suppose it does it? Well, it spins a long web that is so

light that the wind takes it high up into the air. The spider holds on to one end of it and lets go of what it stood on, and so it goes floating along just as if it were in a balloon. In the fall you will see a great many of these

webs in the air. Then these gossamer spiders start on a long journey over the houses and fields and rivers until they reach a warmer climate, where they spend the winter. When the wind blows them against a tree, and the web breaks, they spin another and start again.

"Now, God made the spider for something else than just to look at and talk about. The Bible says,' Ask now the beasts, and they shall teach thee.' So even the little spider can set us an example and tell us how to please God. If we should break that spider's web in the corner, he would spin it right over again, and do it as often as we would break it. The spider works hard, and doesn’t give up because it fails sometimes. And so in our lives we must never give up working for God and fighting against sin.

"Sometimes when we do what is wrong, we feel like giving up and not trying any more. But we must never stop loving and working for Jesus.

He tells us in the Bible that 'even a child is known by his doings, whether his work be pure and whether it be right.' Jesus knows when children love him and try hard to please him; and he will make them very happy in this world, and afterward take them to live with him in Heaven, and give them real palaces to live in a thousand times more beautiful than any king's

palaces in the world.

"And now, suppose we go down stairs, and sister will show you some of the strange things we have been talking about, through the microscope."

Flora L. Palmer.

THE SPIDER'S HOME.

A CERTAIN spider, found in the southern part of Europe, makes a curious cradle to preserve her babies through the cold winter, so that the spider family shall not be exterminated. She makes a silk case somewhat the shape of a balloon upside down, not quite half an inch long, and fitted with a door, or cover, which may be opened, though she leaves it carefully closed. In this are placed the eggs, from which little spiders will come out in the spring. To protect them from enemies and the cold, the anxious mamma makes an outer case of exactly the same shape, only about an inch long, and of course larger all around, also fitted with a closed door. Between the two cases the space is stuffed with a golden-brown colored silk, which she spins herself, and makes it warm and comfortable inside. The whole thing is hung to a bush, and left throughout the winter.

---------------------------------

SPIDERS.

MANY will wonder what can be said that is interesting about "those disgusting creatures." But if instead of crushing under your foot the first one you spy, you will follow it to its home, and there study its habits, you will discover more intelligence in the hitherto despised animal than you have given it credit for.

Even Robert Bruce, by watching a spider, learned a lesson of perseverance, which enabled him to regain the throne of Scotland. And who knows but some of the family may learn by the same means some important lesson in life.

Instead of having the• animal itself described, you will in this talk be 'told some things about their homes and habits. We have all brushed down many a spider's web, little knowing how much labor it has cost the tiny creature to make it, nor suspecting the pleasure it would afford us to watch the operation. These webs are all made of silken threads, which are spun by the animal itself, and are of two kinds,—one a smooth, dry thread which does not stick to the animals' feet, while the other is composed of a gluey substance which adheres to everything it touches. The spider uses the smooth thread to make his scaffolding, and to travel on while building his wed, which is composed of the gluey thread, and entangles in its meshes whatever insect comes in contact with it. These threads, though so minute as to be hardly seen singly, are sometimes comprised of as many as a thousand strands coiled into one, and are very strong for their size. So skillfully do these creatures construct their webs that even a large "bottle fly" finds it very difficult to escape from one before the ferocious householder will pounce upon him and inflict his deadly wound.

After his house is built, the owner destroys most of the smooth threads used in constructing it, and stations himself on one side of the web, where he is apparently asleep. But if you will examine closely, you will see that he is spread out with his eight legs upon as many different threads, and as his feet are the most sensitive part of the body, let any of the threads vibrate ever so slightly, and he is instantly on the alert. He runs rapidly to the center and looks for the cause. If some unwary fly has with limb or wing touched one of those fatal threads, he is immediately pierced' with the spider's poisonous fang, one wound from which will cause death. After the conquest, if the spider is not then hungry, he winds several threads about his prey and bangs it up for a future meal, when he will suck the lifeblood from the body and leave its dry and crisp carcass as a warning to others not to pass that way.

But all spiders do not live in webs nor use their silk for the same purpose. Some, like the one in the picture, build their houses in the ground. These they line with a silken tube, forming at its entrance a movable lid, composed of earth and silk, and attached to the silken lining by a sort of hinge. This

cover closes whenever the spider enters or leaves the house, and so perfectly does it fit that when closed, its existence would hardly be detected. This kind is called the Mining Spider, and is found in the south of Europe. Some species use their silken threads merely to wind around their victims, and others to travel by. They descend by their thread head downward, but climb up on it head upward, rolling it into a ball during the ascent.

When they wish to go from tree to tree, some let go a thread in the direction of the wind, and when their delicate sense of touch tells them it has reached the object, they pass over it. In this way they travel long distances without descending to the ground, their tiny cables being frequently seen in dewy mornings of spring or autumn. Some small gossamer spiders even speed through the air, buoyed up by their light threads.

These little creatures are very cleanly in their habits, spending much of their time in removing the dirt and dust from their bodies by means of tiny toothed combs and brushes, with which they are supplied by nature. Many curious stories are told of their ingenuity and intelligence. A prisoner in the Bastile so nearly tamed a spider that at the call of a musical instrument he would come to devour the flies caught for him by the prisoner.

Many attempts have been made to use their silk in manufacturing, but without success. But though not proving useful in this direction, they are put to good service in some parts of South Africa, where they grow to a large size, and are gathered by the natives for food.

C. H. G.

THE WATER-SPIDER.

THE water-spider is a curious and interesting insect. It leads a strange life. Though really belonging to the earth, and needing to breathe the air, it passes nearly the whole of its time in the water. Several other spiders sometimes go under the water, sustaining life by means of the air which is entangled in the hairs clothing the body.

Their submerged life is, however, only accidental, while with the water-spider it, is a constant habit.

The body of the water-spider is lavishly covered with hairs, which serve to entangle a large amount of air, but it has other powers which are not possessed by any other species. It can dive below the surface, carrying with it a very large bubble of air which is held in place by the hind legs; and in spite of this obstacle to its progress, the spider can pass through the water with great speed.

But the strangest thing about this creature is, that it actually lives under water for a considerable time before it ever sees the land. At some depth below the water, the mother spider spins a dome-shaped cell, or nest, with the opening down- ward. Having made this, she ascends to the surface, and there charges her whole body with air, arranging her hind legs in such a manner that this bubble cannot escape. She then dives into the water, and, going to her nest, discharges the bubble into it. A quantity of water is in this way displaced, and the upper part of the cell is filled with air. She then returns for a second supply, and so proceeds, until the nest is full of air. In this curious house the spider lives, and is able to deposit and to hatch her eggs under the water even without wetting them. And strange to say, the spider itself is never wet ; and though it may be seen swimming rapidly about in the water, yet

the moment it comes out on the land, its hairy body will be found as dry as that of any land- spider. The reason of this is that the minute bubbles of air which always cling to the furred body repel the water, and prevent it from wetting the skin. The eggs of this spider are enclosed in a cup-shaped cocoon, like a circular vegetable dish.

This cocoon is said to contain about one hundred eggs.

The movements of this interesting little creature may be watched by placing one in a dish nearly filled with water.

If possible, some water plant should be placed in the vessel. Here the spider will soon construct its house, and exhibit its curious habits. It must be well supplied with flies and other insects thrown into the water. It will pounce on them, carry them to its house, and there take its meal.

Disgusting and unsocial as spiders are generally thought to be, they are capable of being tamed.

Pelisson, a prisoner in the noted French prison of the Bastile, had a pet spider, which came regularly, at the sound of a musical instrument, to get its meal of flies. A spider-raiser in France is said to have tamed eight hundred, which he kept in a single apartment for their silk.

According to a celebrated German naturalist, it takes 4,000,000 of the extremely delicate threads of a spider's web to make a filament as large as a human hair, and each thread of the spider, as used in the web, is made up of thousands of smaller ones.

Some men have even been saved from death by the spider. When pursued by his enemies, Mohammed once took refuge in a cave, and a spider spun its web across the entrance. His pursuers, coming along a few hours later, and seeing it, thought of course no one could have gone into the cave without breaking the web ; and so they passed on. Thus we see that even the smallest of God's creatures are sometimes instruments for accomplishing wonderful things.

M. E. G

FUN WITH A SPIDER.

SPIDERS in many respects are just like other animals, and can be tamed and petted and taught a great many other lessons, which they will learn as readily as a dog or a cat. But you must take the trouble to study their ways, and get on the right side of them.

during which time I have no doubt he was arranging his plans, he began running round the end of the stick, and throwing out great coils of web with his hind feet. In a few minutes little fine strings of web were floating away in the slight breeze that was blowing. After a little, one of these

threads touched the edge of the tub, and stuck fast, as all spider webs will do.

This was just what Mr. Spider was looking for, and the next moment he took hold of his web and gave it a jerk, as a sailor does a rope when he wishes to see how strong it is, or to make it fast.

Having satisfied himself that it was fast at the other end, he gathered it in till it was tight and straight, and then ran on it quickly to the shore—a rescued castaway, saved by his own ingenuity. Spiders are not fools, if they are ugly; and He who made all things has a care and thought for all. The earth is full of the knowledge of God.

A GENTLEMAN living in the South says [that by watching spiders on his piazza, he saw that they put out their webs at night, but in the morning the webs were gone. After watching early and late, he saw a spider just after daylight slowly wind up his web, pack it away in his mouth, and go off, just like a fisherman taking away his nets.